The Glass That Refused Ornament

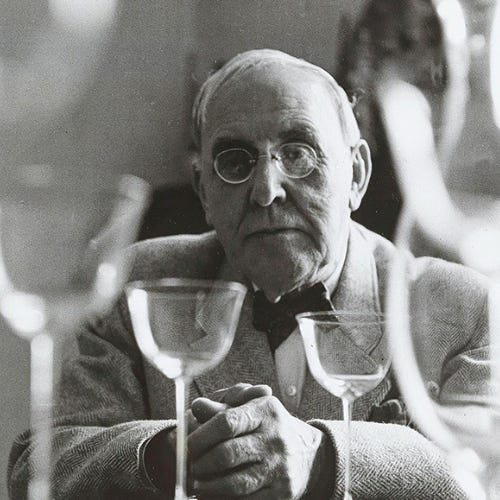

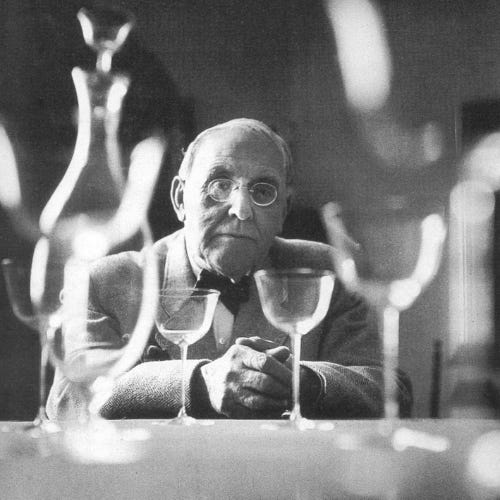

Adolf Loos’s Patrician service for Lobmeyr stripped drinking vessels to their essence — and proved that modernist design could outlast fashion.

In 1917, Josef Hoffmann designed the Patrician service for Lobmeyr. At first glance, it looks almost invisible: a thin-walled bowl, a slender stem, a round foot. But that was its power. Where Lobmeyr had built its reputation on heavy, cut crystal glittering with pattern, Hoffmann offered the opposite: restraint, balance, and proportion.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to THE ART OF LEISURE to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.